GOOD TASTE ALONE

WON'T SAVE YOU

GOOD TASTE ALONE

WON'T SAVE YOU

[AUTHOR]

[AUTHOR]

Andrew Zellinger

Andrew Zellinger

[DATE]

[DATE]

Jan, 6th 2026

Jan 6TH, 2026

Good taste alone won't save you. Judgement alone isn't enough to thrive in the age of AI. There's a narrative gaining traction in design and technology circles. It goes something like this: as AI commoditizes execution, human taste becomes the ultimate differentiator. The ability to discern good from bad, to curate rather than create, to know what should exist—this is what will separate professionals who thrive from those who get automated into irrelevance.

[IT'S A COMFORTING STORY. IT'S ALSO INCOMPLETE]

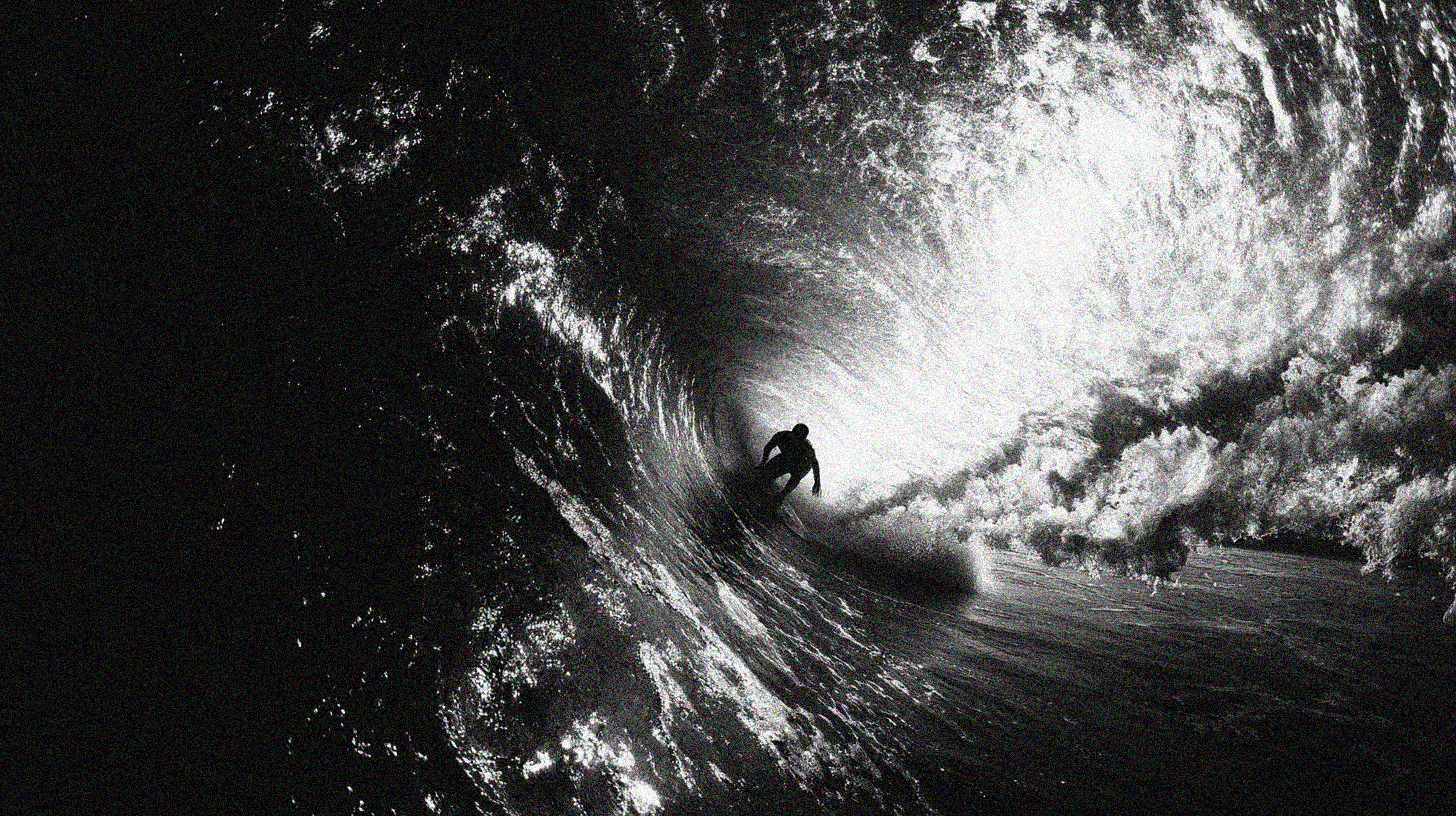

I'm not here to argue that taste doesn't matter. It does. The problem is that taste is being positioned as a life raft when it's actually just one plank in a much larger vessel. And clinging to a single plank in rough water is a poor survival strategy. The professionals who will navigate the next decade successfully won't be those with the most refined aesthetic sensibilities. They'll be the ones who can operationalize their judgment—who understand systems deeply enough to make their taste consequential at scale. Taste without infrastructure is just opinion. And opinion, however sophisticated, doesn't ship products, build businesses, or solve complex problems.

[THE TASTE THESIS, HONESTLY STATED]

Let's steelman the argument before we complicate it. AI tools have gotten remarkably good at execution. They can generate code, produce images, write copy, and synthesize research at speeds that would have seemed absurd five years ago. The mechanical act of making things is becoming cheaper by the month. When everyone has access to the same generative capabilities, the thinking goes, the bottleneck shifts from production to selection. Knowing what to make becomes more valuable than knowing how to make it.

This tracks. When output is abundant, curation matters more. When anyone can generate a thousand variations, the person who can identify the right one holds disproportionate power. The role evolves from craftsperson to editor, from maker to orchestrator. The taste advocates aren't wrong about the direction. They're wrong about what it actually takes to get there.

[TASTE IS AN ABSTRACTION, NOT A SKILL]

Here's the first problem: taste isn't a discrete capability you can develop in isolation. It's an emergent property of other things—domain knowledge, contextual understanding, exposure to both success and failure, and the hard-won pattern recognition that comes from years of seeing what works and what doesn't. When someone demonstrates "good taste" in product design, they're actually demonstrating compressed knowledge about user behavior, technical constraints, business viability, and cultural context. When a creative director makes a call that elevates a campaign, they're drawing on accumulated understanding of brand positioning, audience psychology, competitive dynamics, and execution feasibility. The taste is visible. The substrate is invisible.

This matters because you can't optimize for taste directly. You can only optimize for the inputs that produce it. And those inputs—systems thinking, domain expertise, strategic context—are precisely what the taste-as-salvation narrative tends to overlook. Telling someone to "develop better taste" without addressing these foundations is like telling someone to "be more insightful." It's not actionable. It mistakes the output for the process.

[THE SELF-ATTRIBUTION PROBLEM]

Here's the second problem, and it's more fundamental: everyone thinks they have good taste. This isn't cynicism. It's psychology. Taste is subjective enough that self-assessment becomes nearly impossible. The designer who favors maximalist aesthetics believes minimalists lack sophistication. The minimalist believes the maximalist lacks restraint. Both are convinced their judgment is superior. Both can point to successful work that validates their perspective. If taste is the differentiator, and everyone believes they possess it, what's the actual filtering mechanism? Markets don't reward self-perception. They reward outcomes. And outcomes are determined by far more than aesthetic judgment.

The taste economy thesis assumes that good taste is scarce and identifiable—that the market will reliably surface and reward those who possess it. But taste is culturally contingent, context-dependent, and often only legible in retrospect. The campaign that seemed tasteful and restrained might have been merely forgettable. The choice that felt bold might have been reckless. You frequently can't distinguish between the two until the results are in. This doesn't mean taste is meaningless. It means taste is insufficient as a career strategy. Betting your professional future on a quality that can't be objectively measured, that everyone claims to possess, and that only reveals its value after the fact is not a plan. It's a hope.

[WHAT ACTUALLY DIFFERENTIATES]

If not taste alone, then what? The answer isn't a single attribute but a capability stack—a combination of skills and dispositions that compound over time. Having observed what separates practitioners who consistently deliver impact from those who occasionally produce good work, the pattern becomes clear. It's rarely about who has the most refined sensibilities. It's about who can translate judgment into outcomes reliably, repeatedly, at scale.

System literacy. The ability to understand how things connect—how a design decision affects engineering constraints, how a product choice ripples through business operations, how a creative direction interacts with distribution channels. Taste tells you what's good. Systems literacy tells you what's possible, what's sustainable, and what will actually survive contact with reality. In an age of AI, this extends to understanding how these tools actually work—not at the level of neural network architecture, but at the level of practical capability and constraint. What can current models do well? Where do they fail? How do you construct workflows that leverage their strengths while compensating for their weaknesses? This isn't technical knowledge for its own sake. It's the systems understanding required to make AI a genuine multiplier rather than a novelty.

Domain depth. Taste that isn't grounded in domain expertise is just aesthetic preference. The professional who can look at a solution and immediately identify its flaws isn't exercising some mystical faculty. They've seen enough implementations to recognize the patterns. They understand the problem space deeply enough to know what "good" actually means in context. This is particularly crucial when working with AI tools. The models don't know your industry, your users, your constraints. They produce outputs that look plausible but may be fundamentally misaligned with the actual problem. Domain expertise is what allows you to direct these tools effectively—to prompt with precision, to evaluate outputs critically, to know when the plausible-looking answer is actually wrong.

Strategic context. Taste that ignores business reality is self-indulgence. The most elegant solution is worthless if it doesn't serve the actual objective. Understanding what you're optimizing for—and who you're optimizing for—is prerequisite to any judgment having value. This means understanding stakeholder dynamics, market positioning, resource constraints, and competitive context. It means being able to articulate why a particular direction serves the strategy, not just why it's aesthetically superior. The professionals who consistently deliver impact aren't those with the purest creative vision. They're those who can align creative vision with strategic intent.

Agency and grit. Perhaps most importantly, the ability to actually make things happen. To push through ambiguity, navigate organizational friction, iterate past failure, and ship despite imperfect conditions. The taste discourse tends to emphasize judgment and curation—fundamentally evaluative postures. But evaluation without execution is commentary. The differentiating factor isn't just knowing what's good. It's having the drive and capability to bring good things into existence against all the forces that conspire to prevent it. This is the unsexy truth that the taste narrative glosses over. Success in any field requires grinding through problems that don't have elegant solutions. It requires working with people who don't share your sensibilities. It requires making decisions with incomplete information and living with the consequences. Taste is a component of this. It's not a substitute for it.

[OPERATIONALIZING JUDGEMENT]

The real opportunity in the age of AI isn't to retreat into taste as a protected domain. It's to build systems that make your judgment scale. This is where the conversation should be heading. Not "how do I preserve my value as a tastemaker?" but "how do I construct workflows, processes, and capabilities that allow my judgment to have impact beyond what I can personally touch?" This might mean developing fluency with agentic workflows—understanding how to orchestrate AI tools in sequences that accomplish complex tasks with appropriate human oversight at decision points. It might mean building evaluation frameworks that encode your judgment into repeatable processes. It might mean creating feedback loops that allow you to refine AI outputs systematically rather than one-off.

The practitioners who are thriving right now aren't those who've circled the wagons around "human creativity." They're the ones who've figured out how to amplify their capabilities by integrating AI thoughtfully into their practice. They haven't abandoned judgment. They've found ways to apply it at leverage points where it matters most, while offloading execution to tools that handle it better and faster. This requires learning new skills. Understanding how models work. Getting comfortable with prompt engineering and context design. Building mental models for what automation can and can't do. None of this diminishes the importance of taste. It contextualizes taste within a broader capability set that actually delivers results.

[THE PATH FORWARD]

None of this is an argument against developing your aesthetic sensibilities, your critical faculties, your ability to discern good from bad. These remain valuable. They're just not sufficient. The argument is for expanding your conception of what it takes to succeed. For recognizing that taste is one node in a network of capabilities, not the whole network. For investing in systems literacy and domain depth and strategic thinking with the same seriousness you bring to developing your creative judgment.

The professionals who will thrive in the coming years will be those who can hold multiple frames simultaneously—who can exercise taste and understand systems, who can make aesthetic judgments and navigate business complexity, who can curate and build. This is more demanding than retreating into taste as a safe harbor. It requires continuous learning in domains that may feel foreign. It requires engaging with technical and strategic dimensions of work that creative professionals have historically been able to avoid. It requires accepting that the boundaries of your role are expanding, and that maintaining impact means growing to fill the new space. But it's also more honest than pretending that taste alone will see you through. The transformation underway is real. The tools are getting better. The competitive landscape is shifting. Meeting this moment requires more than pointing to your sensibilities and hoping that's enough. Taste matters. It always has. But taste has always been in service of something larger—a problem solved, a business built, a vision realized. The goal was never the taste itself. The goal was the impact.

[KEEP DEVELOPING YOUR JUDGEMENT. BUT BUILD THE MACHINERY THAT MAKES IT MATTER.]

Taste won't save you. Judgement alone isn't enough to thrive in the age of AI. There's a narrative gaining traction in design and technology circles. It goes something like this: as AI commoditizes execution, human taste becomes the ultimate differentiator. The ability to discern good from bad, to curate rather than create, to know what should exist—this is what will separate professionals who thrive from those who get automated into irrelevance.

[IT'S A COMFORTING STORY, IT's ALSO INCOMPLETE]

I'm not here to argue that taste doesn't matter. It does. The problem is that taste is being positioned as a life raft when it's actually just one plank in a much larger vessel. And clinging to a single plank in rough water is a poor survival strategy. The professionals who will navigate the next decade successfully won't be those with the most refined aesthetic sensibilities. They'll be the ones who can operationalize their judgment—who understand systems deeply enough to make their taste consequential at scale. Taste without infrastructure is just opinion. And opinion, however sophisticated, doesn't ship products, build businesses, or solve complex problems.

[THE TASTE THESIS, HONESTLY STATED]

Let's steelman the argument before we complicate it. AI tools have gotten remarkably good at execution. They can generate code, produce images, write copy, and synthesize research at speeds that would have seemed absurd five years ago. The mechanical act of making things is becoming cheaper by the month. When everyone has access to the same generative capabilities, the thinking goes, the bottleneck shifts from production to selection. Knowing what to make becomes more valuable than knowing how to make it.

This tracks. When output is abundant, curation matters more. When anyone can generate a thousand variations, the person who can identify the right one holds disproportionate power. The role evolves from craftsperson to editor, from maker to orchestrator. The taste advocates aren't wrong about the direction. They're wrong about what it actually takes to get there.

[TASTE IS AN ABSTRACTION, NOT A SKILL]

Here's the first problem: taste isn't a discrete capability you can develop in isolation. It's an emergent property of other things—domain knowledge, contextual understanding, exposure to both success and failure, and the hard-won pattern recognition that comes from years of seeing what works and what doesn't.

When someone demonstrates "good taste" in product design, they're actually demonstrating compressed knowledge about user behavior, technical constraints, business viability, and cultural context. When a creative director makes a call that elevates a campaign, they're drawing on accumulated understanding of brand positioning, audience psychology, competitive dynamics, and execution feasibility. The taste is visible. The substrate is invisible.

This matters because you can't optimize for taste directly. You can only optimize for the inputs that produce it. And those inputs—systems thinking, domain expertise, strategic context—are precisely what the taste-as-salvation narrative tends to overlook. Telling someone to "develop better taste" without addressing these foundations is like telling someone to "be more insightful." It's not actionable. It mistakes the output for the process.

[THE SELF-ATTRIBUTION PROBLEM]

Here's the second problem, and it's more fundamental… everyone thinks they have good taste.

This isn't cynicism. It's psychology. Taste is subjective enough that self-assessment becomes nearly impossible. The designer who favors maximalist aesthetics believes minimalists lack sophistication. The minimalist believes the maximalist lacks restraint. Both are convinced their judgment is superior. Both can point to successful work that validates their perspective. If taste is the differentiator, and everyone believes they possess it, what's the actual filtering mechanism? Markets don't reward self-perception. They reward outcomes. And outcomes are determined by far more than aesthetic judgment.

The taste economy thesis assumes that good taste is scarce and identifiable—that the market will reliably surface and reward those who possess it. But taste is culturally contingent, context-dependent, and often only legible in retrospect. The campaign that seemed tasteful and restrained might have been merely forgettable. The choice that felt bold might have been reckless. You frequently can't distinguish between the two until the results are in. This doesn't mean taste is meaningless. It means taste is insufficient as a career strategy. Betting your professional future on a quality that can't be objectively measured, that everyone claims to possess, and that only reveals its value after the fact is not a plan. It's a hope.

[WHAT ACTUALLY DIFFERENTIATES]

If not taste alone, then what? The answer isn't a single attribute but a capability stack—a combination of skills and dispositions that compound over time. Having observed what separates practitioners who consistently deliver impact from those who occasionally produce good work, the pattern becomes clear. It's rarely about who has the most refined sensibilities. It's about who can translate judgment into outcomes reliably, repeatedly, at scale.

System literacy. The ability to understand how things connect—how a design decision affects engineering constraints, how a product choice ripples through business operations, how a creative direction interacts with distribution channels. Taste tells you what's good. Systems literacy tells you what's possible, what's sustainable, and what will actually survive contact with reality. In an age of AI, this extends to understanding how these tools actually work—not at the level of neural network architecture, but at the level of practical capability and constraint. What can current models do well? Where do they fail? How do you construct workflows that leverage their strengths while compensating for their weaknesses? This isn't technical knowledge for its own sake. It's the systems understanding required to make AI a genuine multiplier rather than a novelty.

Domain depth. Taste that isn't grounded in domain expertise is just aesthetic preference. The professional who can look at a solution and immediately identify its flaws isn't exercising some mystical faculty. They've seen enough implementations to recognize the patterns. They understand the problem space deeply enough to know what "good" actually means in context. This is particularly crucial when working with AI tools. The models don't know your industry, your users, your constraints. They produce outputs that look plausible but may be fundamentally misaligned with the actual problem. Domain expertise is what allows you to direct these tools effectively—to prompt with precision, to evaluate outputs critically, to know when the plausible-looking answer is actually wrong.

Strategic context. Taste that ignores business reality is self-indulgence. The most elegant solution is worthless if it doesn't serve the actual objective. Understanding what you're optimizing for—and who you're optimizing for—is prerequisite to any judgment having value. This means understanding stakeholder dynamics, market positioning, resource constraints, and competitive context. It means being able to articulate why a particular direction serves the strategy, not just why it's aesthetically superior. The professionals who consistently deliver impact aren't those with the purest creative vision. They're those who can align creative vision with strategic intent.

Agency and grit. Perhaps most importantly, the ability to actually make things happen. To push through ambiguity, navigate organizational friction, iterate past failure, and ship despite imperfect conditions. The taste discourse tends to emphasize judgment and curation—fundamentally evaluative postures. But evaluation without execution is commentary. The differentiating factor isn't just knowing what's good. It's having the drive and capability to bring good things into existence against all the forces that conspire to prevent it. This is the unsexy truth that the taste narrative glosses over. Success in any field requires grinding through problems that don't have elegant solutions. It requires working with people who don't share your sensibilities. It requires making decisions with incomplete information and living with the consequences. Taste is a component of this. It's not a substitute for it.

[OPERATIONALIZING JUDGEMENT]

The real opportunity in the age of AI isn't to retreat into taste as a protected domain. It's to build systems that make your judgment scale. This is where the conversation should be heading. Not "how do I preserve my value as a tastemaker?" but "how do I construct workflows, processes, and capabilities that allow my judgment to have impact beyond what I can personally touch?" This might mean developing fluency with agentic workflows—understanding how to orchestrate AI tools in sequences that accomplish complex tasks with appropriate human oversight at decision points. It might mean building evaluation frameworks that encode your judgment into repeatable processes. It might mean creating feedback loops that allow you to refine AI outputs systematically rather than one-off.

The practitioners who are thriving right now aren't those who've circled the wagons around "human creativity." They're the ones who've figured out how to amplify their capabilities by integrating AI thoughtfully into their practice. They haven't abandoned judgment. They've found ways to apply it at leverage points where it matters most, while offloading execution to tools that handle it better and faster. This requires learning new skills. Understanding how models work. Getting comfortable with prompt engineering and context design. Building mental models for what automation can and can't do. None of this diminishes the importance of taste. It contextualizes taste within a broader capability set that actually delivers results.

[THE PATH FORWARD]

None of this is an argument against developing your aesthetic sensibilities, your critical faculties, your ability to discern good from bad. These remain valuable. They're just not sufficient. The argument is for expanding your conception of what it takes to succeed. For recognizing that taste is one node in a network of capabilities, not the whole network. For investing in systems literacy and domain depth and strategic thinking with the same seriousness you bring to developing your creative judgment.

The professionals who will thrive in the coming years will be those who can hold multiple frames simultaneously—who can exercise taste and understand systems, who can make aesthetic judgments and navigate business complexity, who can curate and build. This is more demanding than retreating into taste as a safe harbor. It requires continuous learning in domains that may feel foreign. It requires engaging with technical and strategic dimensions of work that creative professionals have historically been able to avoid. It requires accepting that the boundaries of your role are expanding, and that maintaining impact means growing to fill the new space. But it's also more honest than pretending that taste alone will see you through. The transformation underway is real. The tools are getting better. The competitive landscape is shifting. Meeting this moment requires more than pointing to your sensibilities and hoping that's enough.

Taste matters. It always has. But taste has always been in service of something larger—a problem solved, a business built, a vision realized. The goal was never the taste itself. The goal was the impact.

[KEEP DEVELOPING YOUR JUDGEMENT. BUT BUILD THE MACHINERY TO MAKE IT MATTER]

Good taste alone won't save you. Judgement alone isn't enough to thrive in the age of AI. There's a narrative gaining traction in design and technology circles. It goes something like this: as AI commoditizes execution, human taste becomes the ultimate differentiator. The ability to discern good from bad, to curate rather than create, to know what should exist—this is what will separate professionals who thrive from those who get automated into irrelevance.

[IT'S A COMFORTING STORY. IT'S ALSO INCOMPLETE]

I'm not here to argue that taste doesn't matter. It does. The problem is that taste is being positioned as a life raft when it's actually just one plank in a much larger vessel. And clinging to a single plank in rough water is a poor survival strategy. The professionals who will navigate the next decade successfully won't be those with the most refined aesthetic sensibilities. They'll be the ones who can operationalize their judgment—who understand systems deeply enough to make their taste consequential at scale. Taste without infrastructure is just opinion. And opinion, however sophisticated, doesn't ship products, build businesses, or solve complex problems.

[THE TASTE THESIS, HONESTLY STATED]

Let's steelman the argument before we complicate it. AI tools have gotten remarkably good at execution. They can generate code, produce images, write copy, and synthesize research at speeds that would have seemed absurd five years ago. The mechanical act of making things is becoming cheaper by the month. When everyone has access to the same generative capabilities, the thinking goes, the bottleneck shifts from production to selection. Knowing what to make becomes more valuable than knowing how to make it.

This tracks. When output is abundant, curation matters more. When anyone can generate a thousand variations, the person who can identify the right one holds disproportionate power. The role evolves from craftsperson to editor, from maker to orchestrator. The taste advocates aren't wrong about the direction. They're wrong about what it actually takes to get there.

[TASTE IS AN ABSTRACTION, NOT A SKILL]

Here's the first problem: taste isn't a discrete capability you can develop in isolation. It's an emergent property of other things—domain knowledge, contextual understanding, exposure to both success and failure, and the hard-won pattern recognition that comes from years of seeing what works and what doesn't.

When someone demonstrates "good taste" in product design, they're actually demonstrating compressed knowledge about user behavior, technical constraints, business viability, and cultural context. When a creative director makes a call that elevates a campaign, they're drawing on accumulated understanding of brand positioning, audience psychology, competitive dynamics, and execution feasibility. The taste is visible. The substrate is invisible.

This matters because you can't optimize for taste directly. You can only optimize for the inputs that produce it. And those inputs—systems thinking, domain expertise, strategic context—are precisely what the taste-as-salvation narrative tends to overlook. Telling someone to "develop better taste" without addressing these foundations is like telling someone to "be more insightful." It's not actionable. It mistakes the output for the process.

[THE SELF-ATTRIBUTION PROBLEM]

Here's the second problem, and it's more fundamental: everyone thinks they have good taste. This isn't cynicism. It's psychology. Taste is subjective enough that self-assessment becomes nearly impossible. The designer who favors maximalist aesthetics believes minimalists lack sophistication. The minimalist believes the maximalist lacks restraint. Both are convinced their judgment is superior. Both can point to successful work that validates their perspective. If taste is the differentiator, and everyone believes they possess it, what's the actual filtering mechanism? Markets don't reward self-perception. They reward outcomes. And outcomes are determined by far more than aesthetic judgment.

The taste economy thesis assumes that good taste is scarce and identifiable—that the market will reliably surface and reward those who possess it. But taste is culturally contingent, context-dependent, and often only legible in retrospect. The campaign that seemed tasteful and restrained might have been merely forgettable. The choice that felt bold might have been reckless. You frequently can't distinguish between the two until the results are in. This doesn't mean taste is meaningless. It means taste is insufficient as a career strategy. Betting your professional future on a quality that can't be objectively measured, that everyone claims to possess, and that only reveals its value after the fact is not a plan. It's a hope.

[WHAT ACTUALLY DIFFERENTIATES]

If not taste alone, then what? The answer isn't a single attribute but a capability stack—a combination of skills and dispositions that compound over time. Having observed what separates practitioners who consistently deliver impact from those who occasionally produce good work, the pattern becomes clear. It's rarely about who has the most refined sensibilities. It's about who can translate judgment into outcomes reliably, repeatedly, at scale.

System literacy. The ability to understand how things connect—how a design decision affects engineering constraints, how a product choice ripples through business operations, how a creative direction interacts with distribution channels. Taste tells you what's good. Systems literacy tells you what's possible, what's sustainable, and what will actually survive contact with reality. In an age of AI, this extends to understanding how these tools actually work—not at the level of neural network architecture, but at the level of practical capability and constraint. What can current models do well? Where do they fail? How do you construct workflows that leverage their strengths while compensating for their weaknesses? This isn't technical knowledge for its own sake. It's the systems understanding required to make AI a genuine multiplier rather than a novelty.

Domain depth. Taste that isn't grounded in domain expertise is just aesthetic preference. The professional who can look at a solution and immediately identify its flaws isn't exercising some mystical faculty. They've seen enough implementations to recognize the patterns. They understand the problem space deeply enough to know what "good" actually means in context. This is particularly crucial when working with AI tools. The models don't know your industry, your users, your constraints. They produce outputs that look plausible but may be fundamentally misaligned with the actual problem. Domain expertise is what allows you to direct these tools effectively—to prompt with precision, to evaluate outputs critically, to know when the plausible-looking answer is actually wrong.

Strategic context. Taste that ignores business reality is self-indulgence. The most elegant solution is worthless if it doesn't serve the actual objective. Understanding what you're optimizing for—and who you're optimizing for—is prerequisite to any judgment having value. This means understanding stakeholder dynamics, market positioning, resource constraints, and competitive context. It means being able to articulate why a particular direction serves the strategy, not just why it's aesthetically superior. The professionals who consistently deliver impact aren't those with the purest creative vision. They're those who can align creative vision with strategic intent.

Agency and grit. Perhaps most importantly, the ability to actually make things happen. To push through ambiguity, navigate organizational friction, iterate past failure, and ship despite imperfect conditions. The taste discourse tends to emphasize judgment and curation—fundamentally evaluative postures. But evaluation without execution is commentary. The differentiating factor isn't just knowing what's good. It's having the drive and capability to bring good things into existence against all the forces that conspire to prevent it. This is the unsexy truth that the taste narrative glosses over. Success in any field requires grinding through problems that don't have elegant solutions. It requires working with people who don't share your sensibilities. It requires making decisions with incomplete information and living with the consequences. Taste is a component of this. It's not a substitute for it.

[OPERATIONALIZING JUDGEMENT]

The real opportunity in the age of AI isn't to retreat into taste as a protected domain. It's to build systems that make your judgment scale. This is where the conversation should be heading. Not "how do I preserve my value as a tastemaker?" but "how do I construct workflows, processes, and capabilities that allow my judgment to have impact beyond what I can personally touch?" This might mean developing fluency with agentic workflows—understanding how to orchestrate AI tools in sequences that accomplish complex tasks with appropriate human oversight at decision points. It might mean building evaluation frameworks that encode your judgment into repeatable processes. It might mean creating feedback loops that allow you to refine AI outputs systematically rather than one-off.

The practitioners who are thriving right now aren't those who've circled the wagons around "human creativity." They're the ones who've figured out how to amplify their capabilities by integrating AI thoughtfully into their practice. They haven't abandoned judgment. They've found ways to apply it at leverage points where it matters most, while offloading execution to tools that handle it better and faster. This requires learning new skills. Understanding how models work. Getting comfortable with prompt engineering and context design. Building mental models for what automation can and can't do. None of this diminishes the importance of taste. It contextualizes taste within a broader capability set that actually delivers results.

[THE PATH FORWARD]

None of this is an argument against developing your aesthetic sensibilities, your critical faculties, your ability to discern good from bad. These remain valuable. They're just not sufficient. The argument is for expanding your conception of what it takes to succeed. For recognizing that taste is one node in a network of capabilities, not the whole network. For investing in systems literacy and domain depth and strategic thinking with the same seriousness you bring to developing your creative judgment.

The professionals who will thrive in the coming years will be those who can hold multiple frames simultaneously—who can exercise taste and understand systems, who can make aesthetic judgments and navigate business complexity, who can curate and build. This is more demanding than retreating into taste as a safe harbor. It requires continuous learning in domains that may feel foreign. It requires engaging with technical and strategic dimensions of work that creative professionals have historically been able to avoid. It requires accepting that the boundaries of your role are expanding, and that maintaining impact means growing to fill the new space. But it's also more honest than pretending that taste alone will see you through. The transformation underway is real. The tools are getting better. The competitive landscape is shifting. Meeting this moment requires more than pointing to your sensibilities and hoping that's enough. Taste matters. It always has. But taste has always been in service of something larger—a problem solved, a business built, a vision realized. The goal was never the taste itself. The goal was the impact.

[KEEP DEVELOPING YOUR JUDGEMENT. BUT BUILD THE MACHINERY THAT MAKES IT MATTER.]